Extreme Weather Toolkit: Drought

Rising global temperatures are altering the water cycle and increasing the risk of drought in parts of the U.S.

Climate Matters•October 1, 2025

The relentless rise in heat-trapping pollution is warming the planet and changing the dynamics of drought — and its effects on water security, food supplies, wildfire, and ecosystems.

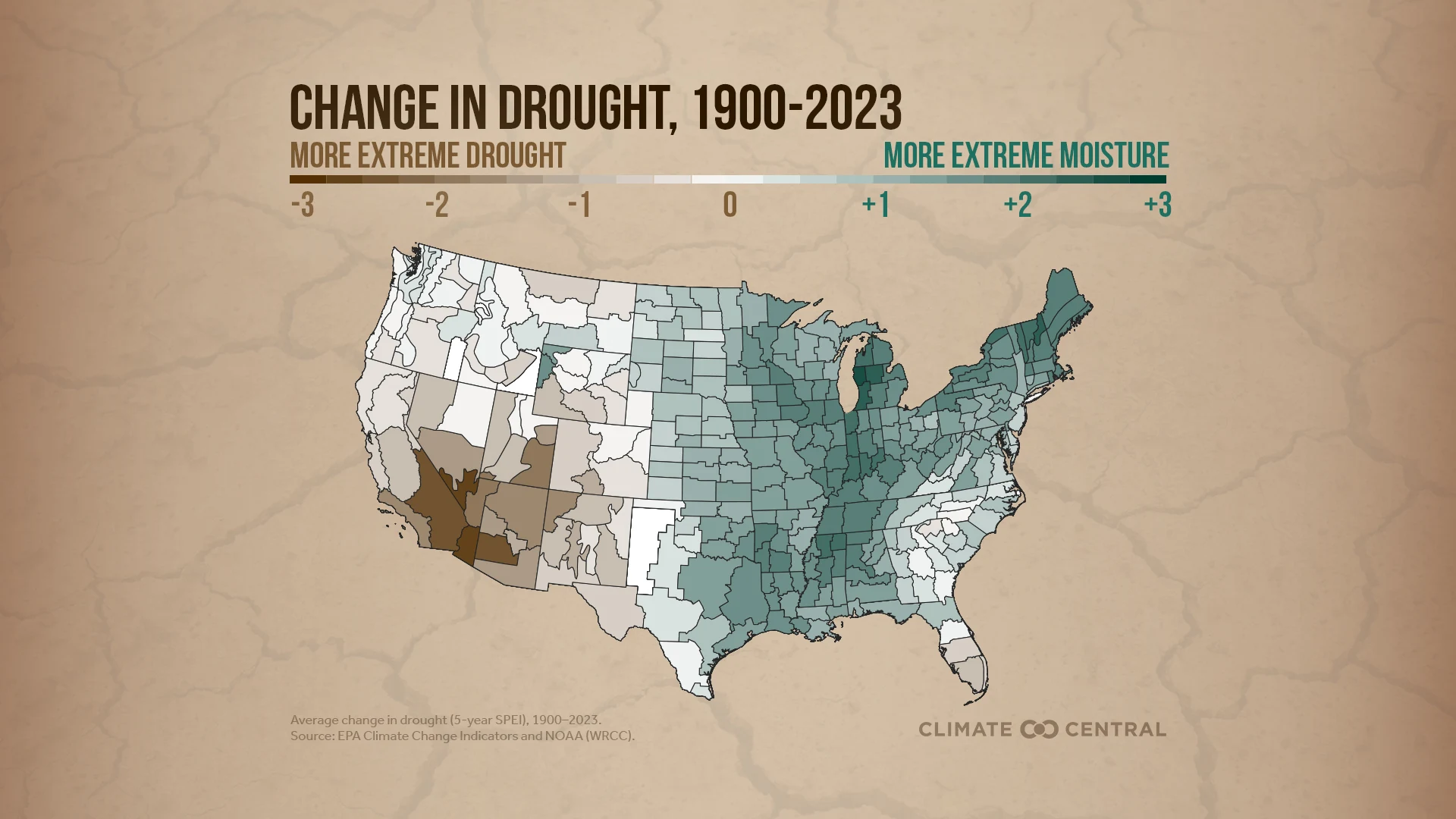

Since the early 20th century, the western U.S. has become drier and the eastern U.S. has become wetter.

As temperatures rise, the atmosphere gets thirstier and pulls more water from streams, soils, and plants — causing or worsening drought and fueling wildfire risk.

Emerging research shows that, in our warming climate, the atmosphere’s growing demand for water is an increasingly important cause of drought in the western U.S. and around the globe.

Historically, a lack of rain and snow was the leading cause of drought in the western U.S. But since 2000, atmospheric thirst due to human-caused warming has taken the lead in driving drought in the region.

This Climate Matters analysis is based on open-access data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Western Regional Climate Center.

Water is vital, but unevenly distributed. Our changing climate is amplifying both extremes of the water cycle, and people around the world are facing the effects of either too much or too little water.

At the start of the new water year (October 2025 through September 2026), the U.S. is also facing the effects of both drought and deluge.

Heavy downpours across the central and eastern U.S. have resulted in a record-setting number of flash flood warnings issued by the National Weather Service in 2025. In the most devastating case, torrential rainfall caused catastrophic flash flooding in the Texas Hill Country in early July, claiming at least 135 lives.

Meanwhile, widespread severe drought across the western U.S. continues to put the region’s water supplies at risk. The Colorado River Basin, which more than 40 million people across seven western states rely on, is entirely in drought. Current operating guidelines for this vital water resource are set to expire in 2026 and negotiations are underway to manage its future.

Climate change is making this more complex than ever. The relentless rise in heat-trapping pollution is warming the planet and changing the dynamics of drought — and its effects on water security, food supplies, wildfire, and ecosystems — in the U.S. and across the globe.

Since the early 20th century, the western U.S. has become drier. The Southwest, along with California and Nevada, have experienced the most extreme drought intensification across the country.

Over the same period, the eastern U.S., and especially the Northeast and Upper Midwest, have generally become wetter.

These trends are reflected in long-term changes in Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) from 1900 to 2023.

The SPEI and other drought indicators reflect the balance between moisture supply (precipitation) and atmospheric moisture demand (evapotranspiration, or the combined evaporation from the land surface and transpiration from plants).

A growing body of research shows that human-caused warming is boosting the demand side of the drought equation — and that the atmosphere’s growing demand for water is an increasingly important cause of drought.

Historically, drought in the western U.S. has mainly been driven by lack of precipitation (mostly rain and snow).

But precipitation is rarely the only climatic factor affecting drought. Another key factor is temperature, and its effect on atmospheric moisture demand — or atmospheric thirst.

As temperatures rise, the atmosphere’s capacity to absorb and hold moisture increases exponentially. In this way, the atmosphere acts like a sponge that grows about 4% larger for every 1°F of warming — both absorbing more moisture from Earth’s surface and raining out more water.

This is how climate warming intensifies the water cycle and amplifies both heavy rainfall and drought.

As warming intensifies and evaporative demand increases further, the finite supply of water from streams, soils, and plants at the land’s surface will eventually fail to keep up with demand — causing or worsening drought.

Heat-driven increases in atmospheric thirst, fueled by human-caused climate change, have been the leading cause of exceptional drought conditions in the western U.S. since 2000.

This period includes an ongoing multi-decade megadrought in the Southwest — the region’s driest stretch in over 1,200 years.

During the later half of the 20th century, drought conditions in the western U.S. were dominated by a lack of precipitation. But a shift in drought dynamics emerged at the turn of the century, fueled mostly by carbon pollution and the resulting warming.

The rising influence of heat-driven drought represents a major shift in western drought dynamics, and one that is projected to accelerate with continued carbon pollution and climate warming.

Because atmospheric thirst increases exponentially with warming, the potential for droughts in the western U.S. to grow longer, larger, and more severe also increases considerably with every bit of additional warming.

Recent research shows that human-caused warming and its effect on atmospheric thirst is:

1. Worsening drought and water stress — globally and in North America

Globally, droughts grew more severe and widespread from 1981-2022. Although a lack of precipitation was the leading cause, atmospheric evaporative demand (i.e., atmospheric thirst) caused about 40% of global drought intensification over this period.

In North America, atmospheric evaporative demand increased significantly from 1980 to 2022. Human-caused climate change accounted for 72% of the rise in atmospheric thirst in the western U.S.

In California's Central Valley — which grows at least half of the country’s vegetables, fruits, and nuts — these effects have increased irrigation demand, further stressing water supplies in this key food-growing region.

2. Slowing drought recovery in the western U.S.

Climate models suggest that recovering from severe drought in the western U.S. currently (2000-2040) takes about one to four months longer than it did in the past (1901-1980) — extending average recovery times to well over one year.

Another 2024 study similarly shows that a warmer, thirstier atmosphere worsens drought risk in the western U.S. in two ways: it not only boosts the odds of drought during relatively dry periods; it also reduces the ability of relatively wet periods to end droughts.

3. Worsening wildfire risk in the western U.S.

Hotter, drier, thirstier air contributes to fire weather and pulls water out of plants, priming them to burn.

In the western U.S., human-caused warming was the leading cause of a fire-fueling rise in atmospheric thirst (as reflected by a rapid increase in vapor pressure deficit) from 1979 to 2020.

In California and Nevada in particular, future warming is projected to increase evaporative demand — and thereby wildfire risk.

The U.S. Drought Monitor (also available in Spanish), a joint effort of the National Drought Mitigation Center, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and NOAA, is a hub for past, current, and forecasted drought conditions across the U.S.

The Drought Impact Reporter Dashboard, maintained by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska, documents and maps county, state, and territory-level drought impacts on a range of sectors including agriculture, energy, public health, fire, and wildlife.

Use the following new resources from the National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS) for the latest drought information in your area during the new water year:

Evaporative Demand Drought Index (EDDI) Subseasonal Forecasts: a drought indicator that uses atmospheric evaporative demand to develop drought forecasts up to four weeks out across the contiguous U.S.

Mississippi River Basin Drought & Water Dashboard: provides interactive and timely data on past, present, and future drought across the basin.

The Western Drought Issue: Throughout Water Year 2026 (October 1, 2025–September 30, 2026), this special communication effort from NIDIS will provide regular updates on water supply risk across the western U.S.

Sign up for NIDIS emails to get drought updates, news, research, and webinars specific to your region.

Rong Fu, Ph.D.

Distinguished Professor

University of California, Los Angeles

Related expertise: North American droughts, rainfall seasonality, and variability

Contact: rfu@atmos.ucla.edu

Emily Williams, Ph.D.

Postdoctoral Scientist

University of California, Merced

Related expertise: Western U.S. drought, climate change attribution

Contact: emilywilliams@ucmerced.edu

Daniel McEvoy, Ph.D.

Associate Research Professor, Climatology

Desert Research Institute

Related expertise: drought monitoring, evapotranspiration and evaporative demand

Contact: Daniel.McEvoy@dri.edu

Submit a request to SciLine from the American Association for the Advancement of Science or to the Climate Data Concierge from Columbia University. These free services rapidly connect journalists to relevant scientific experts.

Browse maps of climate experts and services at regional NOAA, USDA, and Department of the Interior offices.

Explore databases such as 500 Women Scientists, BIPOC Climate and Energy Justice PhDs, and Diverse Sources to find and amplify diverse expert voices.

Reach out to your State Climate Office or the nearest Land-Grant University to connect with scientists, educators, and extension staff in your local area.