Partnership Journalism•August 11, 2025

Aging under a warming planet, how Philly is preparing to support its older population

By Susan Phillips (WHYY) and Melba Newsome (Climate Central)

This story was produced through a collaboration between WHYY and Climate Central. Climate Central researchers Jen Brady, Julia Elman, and WHYY’s Sophia Schmidt contributed reporting.

Blanca Maldonado, 84, steps outside her home in Philadelphia's Fairhill neighborhood. Without air conditioning, she suffers through the hottest days of summer. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

One sweltering day in late July, 84-year-old Blanca Maldonado stretched out on a couch in her North Philadelphia rowhome beneath a ceiling fan and woke up two hours later, unsure whether she’d fallen asleep or passed out from the heat.

“I was soaking wet and I didn’t even know what time it was,” said the recent retiree.

Temperatures that day in Philadelphia neared triple digits, 11 degrees hotter than normal for that time of year — an extreme made twice as likely by climate change, according to Climate Central’s CSI forensics tool. “Because I lost track of the time, that’s why I think maybe I did pass out.”

Maldonado has owned the house in the Kensington section of the city for more than three decades, and although she used to have an air conditioning unit in her kitchen window, it broke and she hasn’t replaced it.

“I like to save my pennies,” she said.

Blanca Maldonado, 84, sits in her favorite chair at her home in Philadelphia’s Fairhill neighborhood. She says this summer has been the worst for heat, but she’s handling the situation. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

A month earlier, in June, the city’s Department of Public Health reported that five people died from heat exposure, when it declared a three-day “heat health emergency” beginning Sunday, June 22. Average round-the-clock temperatures of 88 degrees during that period were much higher than normal. That extreme heat condition had been made four times more likely by climate change, the forensics tool shows.

“In the years I’ve been living here, this year has been the worst. I never experienced heat like this before,” said Maldonado. “But I was younger.”

Climate change is exacerbating the heat risks seniors face. The Philadelphia region is experiencing hotter temperatures, longer summers, and an increase in extreme heat days in our region. Heat waves are becoming more intense, more common and lasting longer. Last year was the hottest year on record, according to NOAA, which also reports the hottest 10 years since records began in 1850, all occurred in the past decade.

A recent climate report from the EPA shows Philadelphia area residents now face an additional four to six heat waves each year compared to 60 years ago.

“Heat waves are natural and expected, but the drastic increase that we’re seeing in the frequency, intensity and the amount of the year that’s taken up by heat waves is absolutely abnormal and is a result of climate change,” said Adam Ortiz, former EPA administrator for the mid-Atlantic region.

Heat’s heavy burden on seniors

Heat is the number one weather-related cause of death of Americans, according to the EPA and the National Weather Service. High temperatures and humidity can cause dehydration, heat exhaustion and heatstroke. Symptoms can include headache, dizziness, nausea, heavy sweating, confusion, weakness and becoming unconscious.

Research has also shown that exposure to extreme heat over time can increase health risks and is associated with a disproportionate increased risk of cognitive decline among Black and low-income people.

“The most important thing we can do … we can drink more water. We can move to an air conditioned area,” said Leah Schinasi, an environmental and occupational epidemiologist and associate professor at Drexel University Drexel who researches how climate change leads to health disparities. “But if your body is not recognizing that it’s really hot outside … then, you know, we’re not going to do them. But then there are people who have cognitive impairment, or they have disabilities. So even if they are recognizing that it’s hot outside, they’re limited in their ability to respond.”

That’s one reason why the city encourages people to check on elderly neighbors during heat waves.

“There’s the classic image of grandmom sitting there with a blanket on her and a sweater and everybody else is dying of heat,” said Philadelphia Department of Public Health spokesman James Garrow. “So if it’s 100 degrees out, a younger person like myself would be sweating, you’d know you feel bad, whereas someone who may be in their 70s and 80s, [may not] have that feedback from their body that’ll tell them, go take a cold shower, go get in the air conditioning.”

Blanca Maldonado, 84, sits in her favorite chair at her home in Philadelphia’s Fairhill neighborhood. A ceiling fan keeps the air moving, but without air conditioning the house gets too hot in the summer. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

High humidity makes it harder for all of us because it decreases the body’s ability to shed heat from sweating. Despite Maldonado’s age, she says she definitely knows when she’s too hot, often feeling as if she might pass out. Her solution is to go to an air conditioned mall or take lots of showers, which is how she managed the July heat wave.

“I was taking a shower at 1 o’clock in the morning, a cold shower because it was awful [that] night,” Maldonado said.

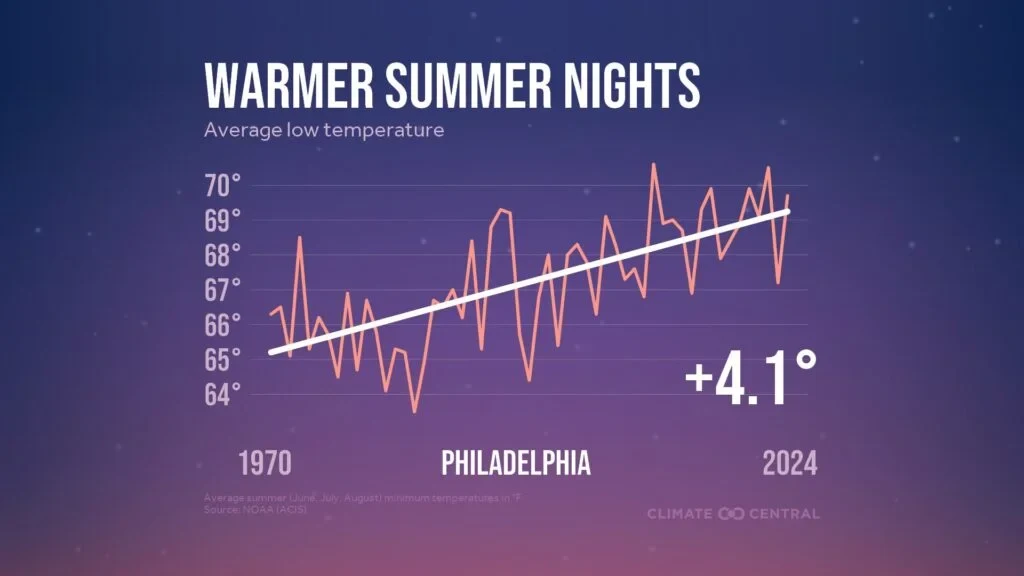

While much of the messaging about extreme heat focuses on the blistering daytime temperatures, a growing body of research shows that overnight heat poses a significant risk to health among those who lack air conditioning.

Ashley Ward, who directs the Heat Policy Innovation Hub at Duke University, says cooler evenings give the body a reprieve from the stresses of severe daytime heat. But if overnight temperatures remain above 75 degrees, our bodies don’t get that relief. “You start to see some pretty extraordinary outcomes with respect to heat illness and heat stroke, and even mortality,” Ward said.

How the city’s built environment exacerbates environmental injustices and health disparities

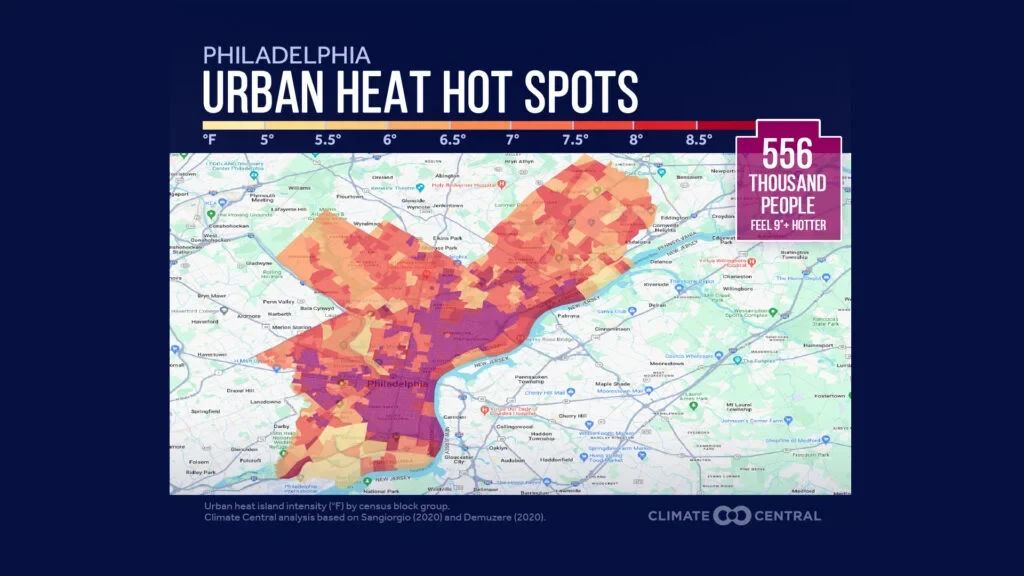

Pavement, black top and dense buildings all contribute to making urban areas hotter than nearby suburbs or the countryside. People of color and those with lower incomes are more likely to live in what is referred to as urban heat islands, which have fewer street trees and parks. These conditions drive up temperatures by at least 9 degrees Fahrenheit for more than half a million people living in Philadelphia, according to a 2024 analysis by Climate Central.

“Within places like Philadelphia, heat exposures are not distributed evenly or equally,” Schinasi said. “People are living in these brick row homes, which I think of as being analogous to a brick oven that just heats up. It’s really, really, hot.”

Schinasi said those residents often have some of the highest rates of chronic conditions that can exacerbate sensitivity to heat, including diabetes and hypertension.

The city maps this disparity through its heat vulnerability index, which shows how some areas with little tree cover and lots of cement — like where Maldonado lives — can increase potential for heat-related illnesses.

Garrow said the city uses the maps to prioritize placement of cooling centers and open public pools. “We want to make sure that those resources are focused in those higher heat areas.”

Blanca Maldonado, 84, stands on the porch of her home in Philadelphia’s Fairhill neighborhood. She suffers through the hottest days of summer without air conditioning. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Maldonado, who takes medication for high blood pressure, lives right in the middle of one of the most vulnerable neighborhoods, marked with a deep red hue on the map.

“It’s not easy, but I’m a strong person, even though I suffer from high blood pressure,” she said. “But sometimes I feel like I’m going to pass out. Sometimes I feel very weak. Two days ago — I started shaking. I thought maybe it was my blood sugar was low or something. But it was just the heat.”

Maldonado, like many who face the greatest dangers, have lower incomes and less ability to pay for air conditioning. Earlier this summer, Maldonado said she got behind on her bills, and her electricity was shut off, but her daughter helped with the payments to get it turned back on.

How rising energy prices hit hotter neighborhoods harder

Maldonado is not alone. Increased demand from data centers and AI last year spurred a jump in prices across the Mid-Atlantic region that kicked in for ratepayers this June, leading to a 38 percent increase in electric shutoffs compared to last year, according to the Pennsylvania Utility Law Project.

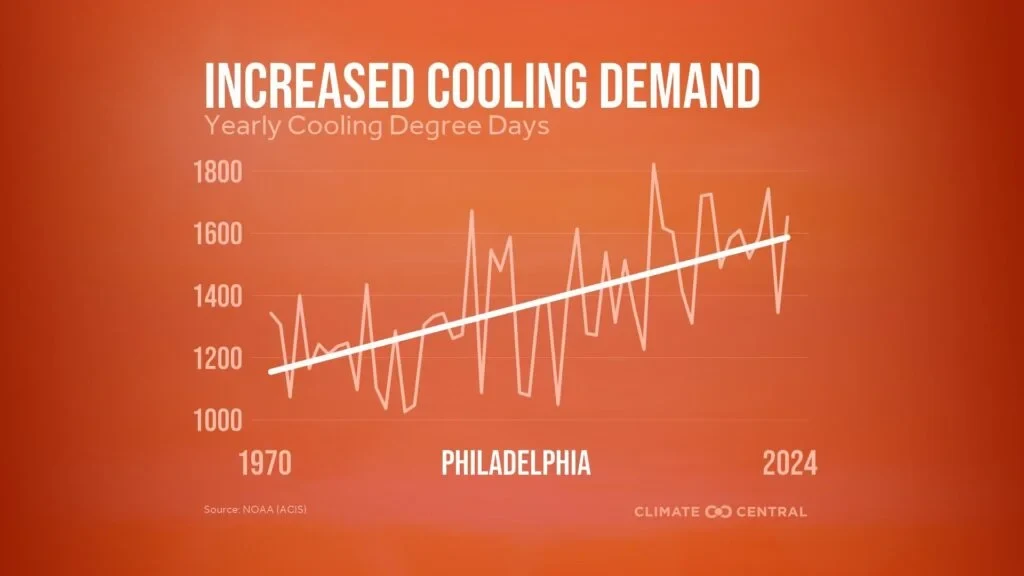

Even as energy prices spike, the amount of electricity needed to keep a home cool continues to rise with the heat. A Climate Central analysis of weather records shows the amount of cooling needed to keep a building comfortable has risen by about a quarter since 1970.

The federally funded Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) helps low-income residents pay for heat in the winter but does not provide funds to help keep electricity on in the summer for cooling. Similarly, while laws prevent electricity shut offs during the winter, that does not apply in the summer. The state recently used money available through the LIHEAP program to pay for window unit air conditioners and repairs to central air for some residents, but the funds lasted for only three summers and were not available this year despite an overwhelming demand.

That shortfall is likely to grow as the need increases. The Trump administration has fired federal workers who administered the LIHEAP program and eliminated funding to local environmental justice communities aimed at adapting to or mitigating the worst impacts of climate change. The recently passed federal budget will limit aid for those who desperately need assistance with energy bills.

Adapting to extreme heat

While getting more air conditioners into these literal brick ovens is the best way to solve the problem in the short term, Schinasi says if you want to tackle climate change, more air conditioning is not sustainable.

Advocates worry that increasing temperatures combined with decreasing social services will increase “energy poverty.” That’s why Schanisi’s research focuses on ways to modify housing to make them cooler without having to crank up the AC. This could be converting dark flat roofs to cooler surfaces, but she said that doesn’t have a large impact for the individual home. Drawing the blinds during the day and incorporating window shades can also help, but not if the humidity is high. Increasing the vegetation in the hottest neighborhoods should also be a priority, she said.

Philadelphia does have programs that promote greening and tree planting, and has initiatives to promote “cool roofs.” During heat health emergencies, the city opens cooling centers at libraries that stay open later and operates a heat line in conjunction with the Philadelphia Corporation for Aging.

“I’m very proud to say that we’ve actually helped save a few lives,” said Nolan Lawrence, PCA’s helpline director, which he said fields several hundred calls a day during heat health emergencies.

The City provides a team of nurses who can do direct intervention if the caller is experiencing serious health issues, like slurring their words, or feeling dizzy. As a result, Nolan said the number of heat-related deaths has dropped significantly since the 1990s.

Blanca Maldonado lives with a parakeet named Mikey. The bird tolerates the heat on the front porch where there is some air circulation. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Maldonado, who turns 85 this month, said since she survived the summer so far, she doesn’t feel the need to invest in an air conditioner this year. Up until November, she was still working as a toll collector, but said she lost her job to automation.

“I’m not afraid of anything,” Maldonado said. “And I never need any help. Like, if I get a flat tire, I change it myself. I thank God I’m still able to do that.”