Climate Matters

Thunderstorm Straight-Line Winds

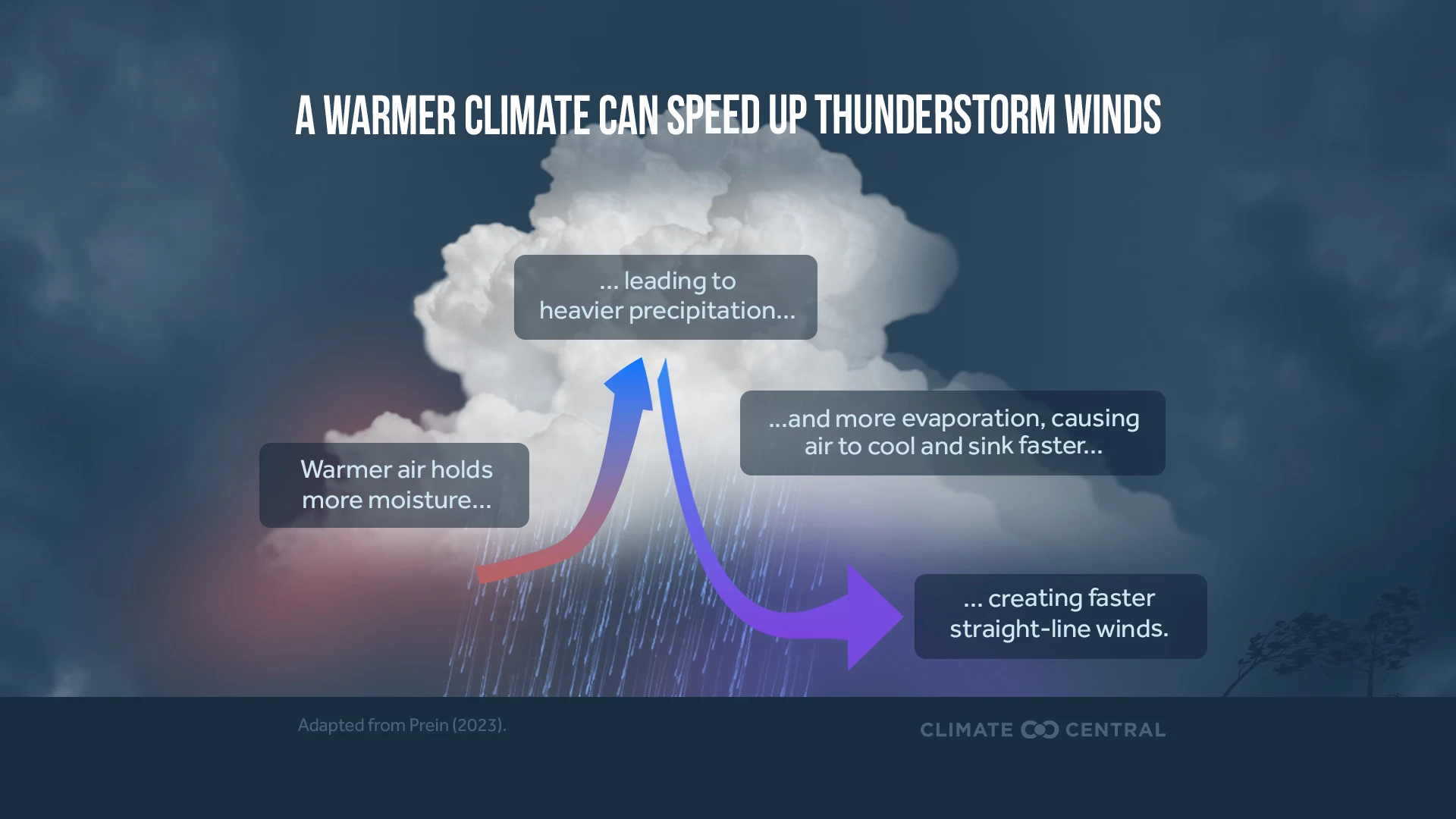

Thunderstorm straight-line winds are the most common severe weather hazard. These destructive and dangerous winds are likely to worsen in a warming climate.

Severe storms — thunderstorms that produce tornadoes, damaging winds or large hail — are destructive and deadly.

Severe storms cause an average of 200 deaths annually in the U.S. and account for half of the total number of billion-dollar weather disasters that have impacted the nation since 1980.

In 2023, the U.S. saw a record-shattering 19 severe storms that each caused at least $1 billion in damages — nearly 50% more than the previous record year (13 storms in 2020). In 2024, there were 17 billion-dollar severe storms in the U.S.

Most U.S. regions face severe weather risks — but risks are especially high in the South, Plains, and Ohio Valley from April through June. People living in mobile homes are particularly vulnerable. Parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Arkansas, Missouri, and Mississippi have seen the most severe weather watches over the last 20 years.

Severe storms are localized, short-lived events with limited historical records. And most climate models are too coarse to accurately simulate such events.

Those two realities together make it difficult to identify if and how global climate change is affecting severe storms. The relationship between severe storms and climate change is an active area of research.

Here’s what we do know:

More frequent and costly billion-dollar severe storms

The U.S. experienced over five times more billion-dollar severe storms during 2005–2024 (168 events) than during the previous two decades (30 events from 1985–2004). The average annual cost (CPI-adjusted) of billion-dollar severe storms has also risen – from $3.8 billion (1985–2004) to $21.8 billion (2005–2024).

Tornado trends

When excluding the weakest events, the overall number of U.S. tornadoes each year hasn’t changed since 1970. But tornado activity has become concentrated in more frequent outbreaks (days with multiple tornadoes). Further, the frequency of U.S. tornado outbreaks is increasing faster for the most extreme outbreaks.

There is also evidence that tornadoes are getting more powerful in the U.S. and that their seasonality is shifting, with summer tornado activity decreasing and fall tornado activity increasing — especially in the Southeast. And “Tornado Alley” has shifted eastward since 1979, with increased tornadic activity observed in the South, Southeast, and Ohio Valley. There’s no clear connection between these observed trends and climate change, however, and trends in the U.S. are not necessarily matched by trends elsewhere in the world.

Thunderstorm trends

Severe storms are more likely to form under certain conditions — including high wind shear and convective available potential energy (CAPE). Since 1979, parts of the eastern U.S. have seen up to 15 more days with high CAPE during spring and summer — prime time for thunderstorms.

But CAPE is just one of several important factors in severe storm formation and it’s unclear how other factors such as wind shear could respond to future warming. Long-term trends show that the frequency of severe and tornadic thunderstorms hasn’t changed significantly since 1979 over multiple U.S. regions.

Future potential

Studies suggest that conditions favorable to severe thunderstorms will become more frequent with continued warming over the 21st century. Estimates suggest a 5-20% increase in favorable conditions per 1.8°F of warming, though patterns vary across the globe. Whether these changing conditions will ultimately result in the formation of more severe storms remains an active area of research.

A 2023 study projects a 6.6% increase in supercell frequency nationwide — and especially in the densely-populated eastern U.S. — by the end of the century as a result of climate warming.

Updated: August 2025

These resources explore the science, trends, and local impacts of severe weather in the U.S.

Search our resource library