Partnership Journalism•July 11, 2025

Rising NJ heat threatens pregnancies

By Melba Newsome (Climate Central) and Lilo H. Stainton (NJ Spotlight News)

This story was produced through a collaboration between NJ Spotlight News and Climate Central. Julia Elman (Climate Central) contributed data reporting.

Flight attendant Treniece Bynum was more than eight months pregnant with her third child when the early weeks of summer hit New Jersey with triple-digit temperatures.

“It was terrible!” said Bynum, a 37-year-old resident of Union Township, less than 10 miles southwest of Newark. Scorching local temperatures during the week of June 22 were made three times more likely by the effects of climate change, according to Climate Central’s Climate Shift Index. “I was drinking water and going to the bathroom like crazy just trying to stay hydrated.”

Keeping cool is a struggle for many pregnant people because the body has a harder time regulating its core temperature during gestation. Growing research warns extreme heat can also harm maternal and infant health, contributing to lower birth weights, increases in preterm births and stillbirths, and increased hypertension among mothers. Rising global temperatures are amplifying the dangers.

Temperatures exceeded thresholds risking preterm births more than 22 times annually in Newark on average during the past five years, according to a Climate Central analysis that used methods developed by academics. Of those, a forensic climate analysis shows more than half were tipped over the temperature threshold by the heat-trapping effects of carbon pollution.

Who’s in most danger?

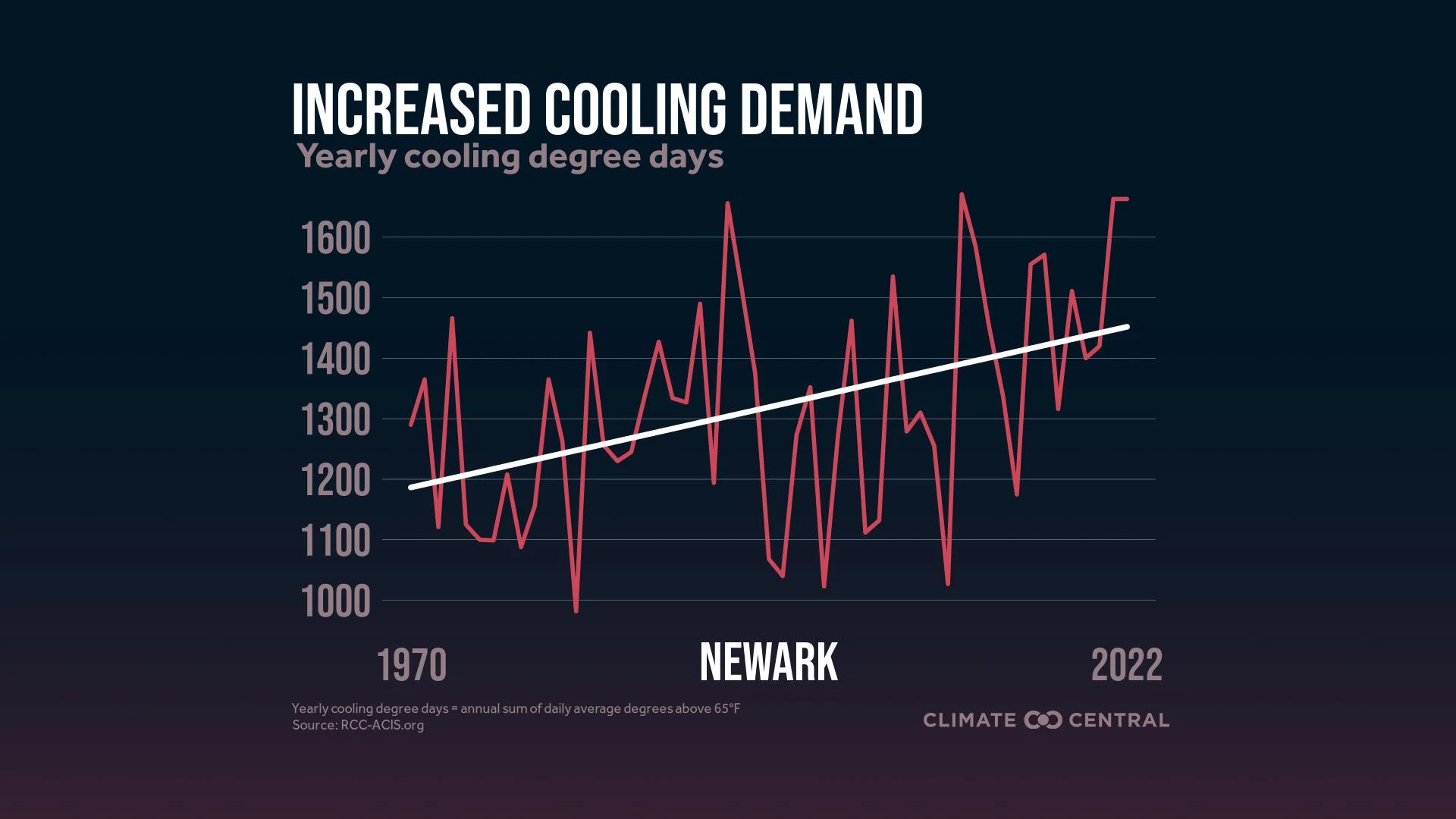

Those who face the greatest dangers have lower incomes and less ability to pay for air conditioning. As temperatures have risen in recent decades, the need for cooling has only grown.

The effects of structural racism mean the most vulnerable pregnant people are often members of communities of color occupying urban corridors devoid of tree canopies that can reduce local temperatures.

Bynum carried all three of her pregnancies through the hottest summer months. Despite being extremely uncomfortable, she wasn’t aware that the high temperatures carried additional health risks for her and the babies.

Climate Central’s analysis of data from more than 200 countries and nearly 1,000 cities, published this past spring, identified the number of days temperatures reached local thresholds where dangers of preterm births increased. Statewide, New Jersey faced an average of 22 pregnancy heat-risk days, while Atlantic City — the other municipality the group examined — experienced 20. In both cases, more than half of those pregnancy danger days were found to be driven by the effects of climate change.

A 2017 paper by a pair of George Washington University researchers concluded that the impact of extreme heat on a mother or baby may be immediate, delayed or cumulative, and that risks appeared to increase globally. “Regardless of the relative warmth of the climate, excessive heat exposure resulted in adverse birth outcomes across the majority of studies in this review,” they wrote.

“Overwhelmingly, what we see is heat increases underlying risk,” said Ashley Ward, the director of the Heat Policy Innovation Hub at Duke University, who has spent much of her career researching issues that are often overlooked, like the dangers of rural heat and nighttime temperatures to maternal and infant health.

According to the most recent federal data, New Jersey’s maternal mortality rates exceeded the nationwide average from 2018 through 2021. Older mothers tend to face higher danger of heat-related maternal health problems. But the risk is even greater among women of color.

Black women are nearly seven times more likely to die during childbirth — and Hispanic women 3.5 times more likely — when compared with white women, according to a review of New Jersey data.

Race, economics, geography

Racial, economic and geographic factors tend to play a large role in these disparities. Wealthier mothers are more likely to live on shady, suburban streets and in air-conditioned homes. Lower-income families are more likely to face the urban heat-island effect, with concrete, pavement and other surfaces absorbing and retaining heat.

Many who can afford it install central air conditioning, such as Rebecca Webber of Maplewood Township, also not far from Newark, who has two young children.

Webber’s 4-year-old son was born in February 2021. She was pregnant with her daughter through the hottest days of summer and gave birth in September 2023. During her pregnancies, even routine tasks seemed too much.

“You just want to sit down and do nothing,” Webber said.

But doing nothing was not an option for her most of the time. The 41-year-old and her husband, Donald, were cast members in the touring company performing the musical “Hamilton.” “We were on the road, performing every day,” she recalled. “It was so hot! The first thing we did when we got home was install central air.”

Growing disparities in access to cooling are largely driven by rising costs of electricity. Installing central air is an unaffordable luxury for many low- and moderate-income residents like the flight attendant Bynum, who said her summertime power bills jump to hundreds of dollars per month.

Bynum’s is among the careers that can compound health threats to pregnant women, with flight attendants often on their feet and vulnerable to dehydration and other stresses. New Jersey is home to a substantial agricultural industry, and pregnant women working outdoors in farming, landscaping and other jobs also face heavy burdens.

“I have such a small space — a two-bedroom apartment that’s less than 1,000 square feet,” said Bynum. “I’m just trying to make one air conditioner work for the whole apartment — make sure a little bit of air gets throughout the whole place, so I cranked it up, but I paid for it the next month.”

Help available

Federal, state and local governments, as well as nonprofits, have implemented programs to assist people who experience energy poverty, the struggle to afford adequate and reliable energy for their homes. But advocates fear federal workforce and funding cuts now endanger some of these programs.

Jennie Sherlock-Loeb, a perinatal nurse and clinical director of The Cooperative, a maternal and child health consortium in South Jersey, says the nonprofit helps connect families with free or discounted air-conditioning units and refers them to local cooling centers and will even pay for a car service, if needed. Nurses making home visits also advise pregnant women and new mothers on warning signs of heat risk, including headache, dizziness and swelling of hands, face or limbs.

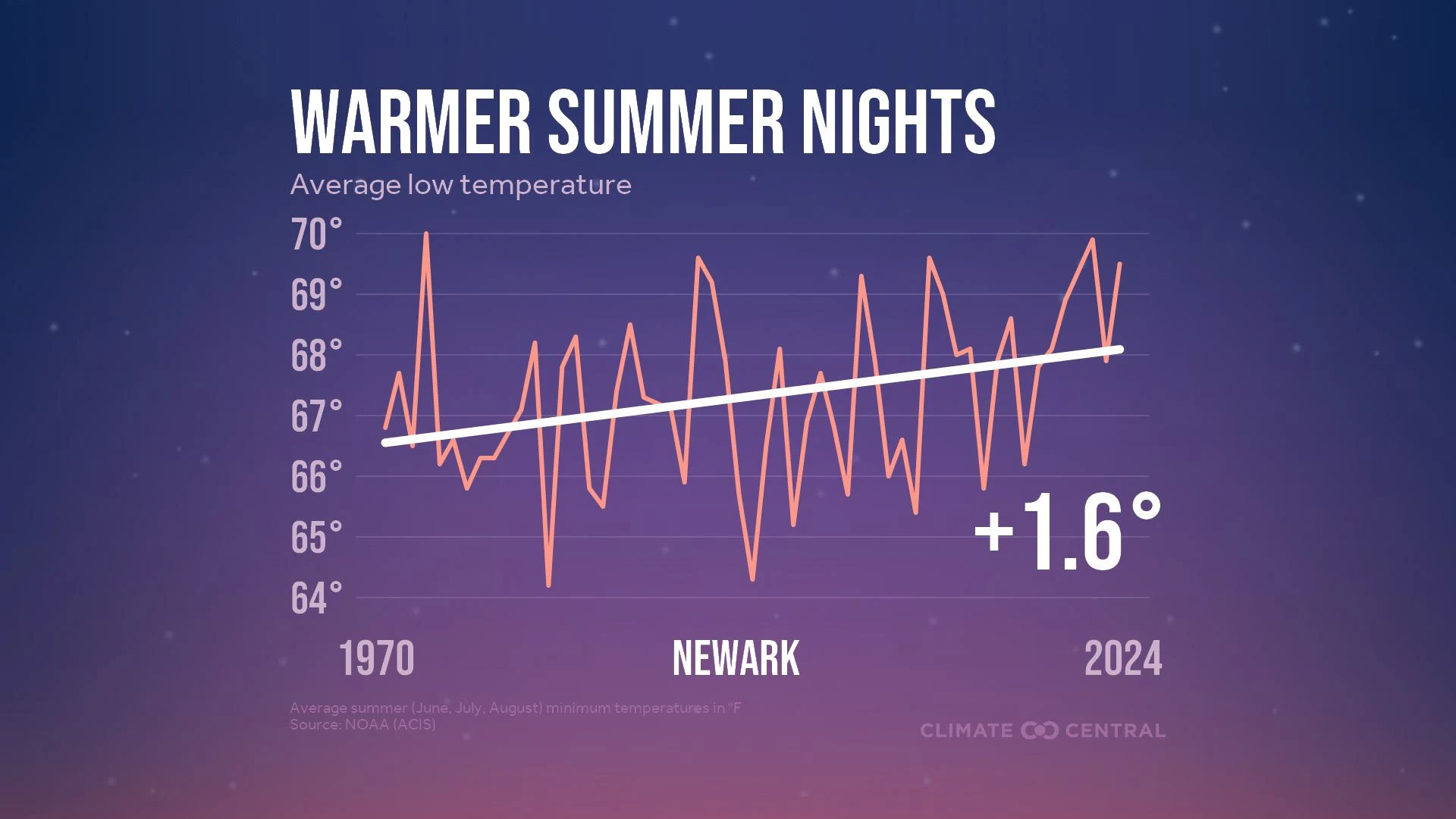

While much of the public messaging around high heat tends to focus on extreme daytime highs, Ward’s research shows that overnight heat poses a greater risk of preterm birth. She advises families to make cooling the bedroom a priority.

“A lot of people might think, ‘I’m going to use this air conditioning to cool off my family room, where we all gather,’ but it’s more important for your health outcomes that you cool your bedroom,” said Ward, with Duke University. “That’s where you sleep, that’s where you’re going to get most of your recovery.”

When overnight temperatures remain at or above 75 degrees Fahrenheit overnight, there is a 4% increase in preterm births — babies born before 37 weeks, instead of the full-term gestation of at least 39 weeks — the days that follow, according to research conducted by the Heat Policy Innovation Hub. Overnight temperatures at or above 80 degrees were found to increase the preterm birth risk by 7% to 8%.

Although New Jersey is the most densely populated state in the nation, much of South Jersey and northwest counties are rural, some with high poverty rates and lower health outcomes than the state at large. Maternal health-care options are also limited in many of these communities.

Rural risk

“What most people don’t know is that heat illness rates are actually five to seven times higher in rural communities than in urban communities,” said Ward. “In my studies, maternal health outcomes are worse and preterm birth rates are higher in rural communities than in urban communities.”

Ward said more needs to be done to warn pregnant women of the risks they and their babies face as temperatures rise. Currently, heat warning systems are triggered at levels much higher than those that affect health outcomes for vulnerable people, she said.

“The systems we have in place are not warning people in time,” said Ward. “The National Weather Service will warn people when the temperature is going to be between 95th or 98th percentile of what’s expected for those regional climates but we actually see health outcomes happening at 88 to 92 percentile.”

Research by Dr. Stefania Papatheodorou, an obstetrician and associate professor at Rutgers School of Public Health who studies environmental impacts on fetal and infant health, indicates that pregnant women’s exposure to extreme temperature is associated with smaller limbs, torsos and skulls in the babies they carry. Her team is now designing a study to understand what it means and why it is happening.

“In general, smaller fetal growth is associated with adverse outcomes,” Papatheodorou said. “We know that from other studies,” she said, “but we have to look closer at what is the mechanism that explains this deviation.”

Papatheodorou and others caution pregnant women and new moms to avoid the impact of extreme temperatures by limiting their time outdoors, seeking air-conditioned spaces and staying hydrated. She also says there are simple steps an individual can take to reduce their heat risk level, most of which involve water. Wrapping yourself in towels soaked in cool water, as well as soaking your feet, arms and elbows in a basin can help.

“These simple things on an individual level can work,” Papatheodorou said. Bigger systemic changes, like making sure everyone has access to air conditioning are more of a challenge, she said. “These are more complicated.”

“What a great world it would be if everyone had access to affordable cooling,” Ward said.